BY BOB KERR, Providence Journal

Journal Columnist

bkerr@providencejournal.com

Vic Del Regno’s film celebrates the letter, the one that is sometimes held and savored before opening. It celebrates the way the letter can survive and be unfolded in its yellowed, crinkly old age and open up the past in ways that can be sweet, jarring, reaffirming.

Del Regno’s “Till Then” will be shown Thursday at The Vets in Providence as part of the Rhode Island International Film Festival. It is part of a festival tradition of deeply personal work that is often years in the making and shows war from seldom-seen angles.

“What kept me going is the message contained in the letters,” says Del Regno, a retired business executive who lives in South Kingstown. “It’s the emotional cost of war — love, betrayal, forgiveness, tragedy and great expectations.”

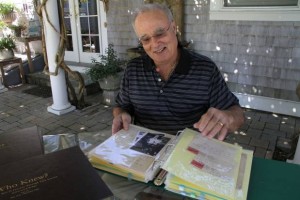

Frieda Squires/The Providence Journal

Vic Del Regno, of South Kingstown, looks through some of the letters written by his parents, Andrew and Helen Del Regno, when his father was stationed in the Pacific during World War II.

The letters are those written by his mother, Helen, and his late father, Andrew, during the two years that his father served with the Seabees in the South Pacific during World War II. Del Regno and his sister found the letters in the attic of the family house in Nyack, N.Y. The letters were moved around some until Del Regno took them from the trunk in which his wife, Theresa, had put them and started sorting through the treasure of family history.

Some of the letters were stained, mildewed.

“I had to unfold them very carefully,” he says.

That was more than five years ago. Since then, the war letters of Andrew and Helen Del Regno have been compiled in a book and become material for a movie. They have become a way to learn about those uneasy, expectant moments when a man or woman seeks out a quiet place to sit down and read of things back home or “over there.”

It seldom happens anymore, of course. There is email now and Skype and the chance to know right away. But once, at least through the Vietnam War, the letter on paper, in an envelope, was the treasured connection. It was the small thing reached for during mail call and held tightly for its warm promise. It sometimes took weeks to get where it was going.

And that sense of handwritten words sent halfway around the world at times of hard uncertainty is at the heart of “Till Then.” It is a film carried by the eloquence of a man who left school in the eighth grade to go to work — and a woman who married young and was left alone at a time when the world was turning over.

When Del Regno began to read his parents’ letters, he was taken back to the time when the war took his father away from his job as a house mover in Nyack to train with the 35th Seabee Battalion at Davisville. It was a time when Nyack was becoming a major troop embarkation point and soldiers filled its streets and bars and tried out their best lines on local women.

And in those two years, there was the worst of times for Andrew Del Regno when his buddies were getting piles of letters and he was getting none. He couldn’t call. He couldn’t email. He could only wait and agonize over the possibilities.

Then came a letter from a friend in Nyack telling him that his wife had been seen with soldiers in hotels. In response, a tent-mate wrote Helen and asked, “How could you do this?”

They worked it out. It’s all there in the letters. Helen asked for forgiveness and Andrew forgave her. After he returned from the Philippines, where he’d been sent to prepare for the invasion of Japan, the Del Regnos settled down and raised six children.

And decades later, Vic Del Regno took those letters — and envelopes,pictures and postcards — and had them beautifully bound in books he titled “Who Knew: A World War II Journey Through Love Letters.” Then he set off on a journey of his own that would take him back to Nyack and to the islands in the South Pacific where his father served in the blistering heat and dove for cover during Japanese attacks and waited for mail call.

When he realized there was a film in those letters, Del Regno got together with Tim Gray, who has produced wonderful World War II documentaries through his company, Tim Gray Media. Gray got to work with Del Regno, writing and planning the locations where they would shoot. They parted ways because of disagreements over the direction the film should take, but Del Regno says he is grateful for the work Gray did, and Gray is listed in the credits as writer and consultant.

Del Regno became director and producer. He became a filmmaker and learned about B-rolls, needle drops, single card credits and spotting notes. He filled a pile of notebooks and spent thousands of hours viewing and editing. He also spent more than $400,000.

It was his dermatologist’s daughter who cleared the way to make the Mills Brothers’ “Till Then” the title track of the movie. She works in Los Angeles and knows how to do such things. The cost was negotiated down from a ridiculously high initial figure.

It was Russell Erwin, a collector of World War II memorabilia from East Providence, who lent authenticity to the reenactment staged at the Seabee Museum at Davisville. He provided vintage everything, including guns, fatigues, cigarettes and skin mags.

It was Ariel Kook and Michael Borges, actors recruited from Theater By The Sea, who played Helen and Andrew Del Regno, adding the proper dramatic touch to the words in those letters.

In Nyack, Del Regno talked to people who remember the war years and how the town was a small and friendly place where everybody knew everybody — until all those soldiers showed up.

In 2010, he went to the Solomon Islands and the tiny island of Banika, where his father spent so much of his time, with photographer and editor Chris Simmons.

“Chris was with me every step of the way on this project,” Del Regno says.

It is in the islands that Del Regno brings the two worlds of his parents’ letters together. He walks Seabee-built roads in the withering heat and sees the rusting remnants of tanks and other war hardware steadily consumed by jungle. He meets with people whose lives have not changed a great deal since their grandparents and great-grandparents dealt with war right outside their doors.

He gives New York Yankee shirts to island residents who, he had learned, like all things New York.

He tosses a flowered wreath into the ocean.

“It was an incredible feeling to go where my father was, and to try to feel what he felt — to be so far away and to wait for a letter.”

This is a very good film, in part perhaps because it is not the work of a professional filmmaker. It is the work of someone who believes he has some history in his hands and it would be wrong not to share its lessons.

“Till Then” is scheduled to be shown at 6:30 p.m. Thursday at The Vets, One Avenue of the Stars.